Companies live and die by innovation: those that invest in it prosper, and those that don’t become obsolete. Even monopoly power does not create a moat to defend against innovation: the railroad companies’ monopoly power did not prevent their industry being overtaken by the rise of the automobile and aviation.

Innovation comes in two flavours: technological and business model innovation. The former is about developing new products (e.g. driverless cars, disposable nappies) , or investing in technology and know-how that makes manufacturing or distribution cheaper or better in some way (e.g. assembly lines). The latter is about doing things in a fundamentally different way (often facilitated or enabled by new technology).

Conventional wisdom has it that the older an industry is, the more ripe for technological disruption it becomes. I don’t think this is quite right. I don’t have any data on this, but I think incumbents in any industry are more likely to develop better products & to improve their operations — even if they don’t innovate themselves, they’ll quickly copy a new entrant’s technology, and use their scale and know-how to beat them. But it is true with regards to business model innovation: incumbents are unlikely to come up with new business models, because a new business model will probably disrupt an incumbent’s existing operations. As per the innovator’s dilemma, this gives new entrants the opportunity to enter a market by targeting under-served customer segments. For example, razor & blades subscription services such as Dollar Shave Club managed to grow, not because incumbents like P&G were stupid and didn’t spot them, but because they were reluctant to enter the DTC space and compete with retailers, who were their biggest customers.

Still though, it seems to me that this kind of business model disruption is likely to take place in industries that are not nascent, but aren’t ancient either: not to sound too much like a Chicago economist, but if an industry has been around for a long time without business model innovations, odds are there is a reason for this: there must be strong barriers preventing new entrants with innovative models from entering the market.

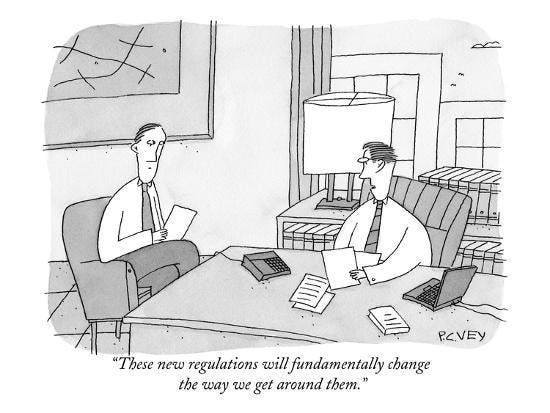

There is no stronger entry barrier than regulation: if entering a market is prohibited by government fiat, that market will remain impregnable. And there are few industries more heavily regulated than finance. It is therefore not surprising that some of the most breakthrough innovations in finance over the past century owe their commercial success to regulation: either they have been conceived as a means of circumventing the law, or regulation has inadvertently spurred consumers to adopt new products.

At least, that’s the key lesson I took from Joe Nocera’s A Piece of the Action. Nocera describes how America gradually turned from a nation of savers to a country of investors and borrowers. There are several examples of regulation spurring innovation in the book:

Credit cards may have originally been created to address customer needs, but a key reason so many banks rushed to issue them, and promote them so aggressively (through, e.g., sending unsolicited cards to tens of thousands of people) was that credit cards allowed banks to expand — something that banking regulations prohibited (for instance, at the time, banks were not allowed to offer whatever interest on deposit they wanted; they could not open branches outside their own states; in some states, banks were only allowed to operate in one city, and in Texas banks were only allowed to have one physical location).

Banks began to change their corporate structures and relocate divisions across the country, based on which states were willing to abolish usury laws. (Speaking of corporate structure alchemy, executives at Gulf + Western figured out how to get around strict regulations preventing non-banks from buying a bank: they realised that in legal terms, a bank was an institution that accepts deposits and makes commercial loans. So they bought a tiny bank, and scrapped its commercial loans business. This led a wave of financial engineering, with everyone from construction companies to piano manufacturers buying banks.)

Money market funds were invented to circumvent Regulation Q: this was regulation drafted in the wake of the Great Depression, when the thinking was that the huge number of bank failures of the era was due to the high interest rates banks offered to depositors. Regulation Q limited the interest banks could offer their customers, so fund companies created funds that strongly resembled bank accounts, especially after Fidelity created a money market fund against which consumers could write cheques.

Similarly, cash management accounts modified money market funds by allowing the customers of the brokerages that offered them to use a credit card linked to their accounts. These were seen as a naked attempt to sidestep regulations, and were challenged by banks.

Discount brokerage houses such as Charles Schwab emerged after the New York Stock Exchange deregulated its commission-fixing system, which had until then prevented brokerages from competing on price (granted, the exchange was not a government entity, so this isn’t strictly speaking regulation, but given its near-monopoly status, I think the argument stands).

The public’s interest in investing was accelerated through the introduction of Individual Retirement Accounts (IRAs); these allowed US citizens to lower their taxable income by parking up to $2k annually in them. This money could not be withdrawn until retirement, but it could be moved around across different companies — e.g. a person could move their IRA from their bank to an investment company. And that’s what many people did: they saw IRAs as a way to experiment with money they couldn’t withdraw, and started channeling them to investments.

There are plenty more examples across the finance industry, including in investment banking, where financial instruments, deals, and financing approaches are often designed to take advantage of some regulatory or tax loophole.

Of course, financial innovation as a means of circumventing regulation brings us to…

Crypto

Crypto is the latest financial product to fit this bill. Crypto evangelists like to claim that crypto is inherently superior to fiat currency and traditional payment rails, but it doesn’t take a doctorate in finance to see that this isn’t true. In reality, the advantages crypto has over traditional finance are derived entirely from the fact that traditional finance is regulated (or that older financial institutions have made the deliberate choice to prioritise consumer protection over speed and efficiency).

Consider this article that lists the benefits of crypto over traditional finance; every single benefit listed is regulation or choice-driven:

Fast: Cryptocurrency transactions are simply much faster and have less [should I be a dick and write ‘sic’? Yes.] barriers

The article claims crypto transactions are faster and have fewer barriers. This is generally not true —as far as I can tell, Visa can process 16x transactions/sec compared to the fastest crypto rail. To the extent some crypto transactions are settled faster than traditional ones, this is not because to technological superiority, but due to the fact that most traditional methods involve regulatory and compliance checks. These are in place to ensure that money isn’t being laundered or channeled to illegal activities.

Cheap: Fewer parties in a transaction mean reduced costs

The cost to a user of a service is equal to the costs of providing the raw service + additional costs related to the service + the provider’s profit margin. The article is correct in saying that when crypto rails are not set up by profit-seeking organisations, this last element is removed, and in this, crypto rails have an advantage over traditional mechanisms.

It is much more debatable whether crypto provides a cheaper service from a technological viewpoint; as per the previous point, this is unlikely to be true (granted, some aspects of traditional finance (such as international transfers) have developed rather chaotically, and are not optimal; but in principle, I think a narrow-scope centralised system will always be more efficient than a decentralised one).

So, so far, crypto is probably tied against traditional finance; where it gains the upper hand is the second element above, additional costs; traditional finance incurs these either because of regulations that require checks and balances (for instance, money transfers have to be screened to ensure they are not made to persons or entities on sanctions lists), or because companies incur costs protecting their consumers (for instance, banks and card companies will reimburse users who have fallen victim to fraud).

Inclusive: Crypto has a low barrier to entry — you only need a mobile phone and an internet connection

This is the most obvious benefit stemming from crypto circumventing regulation. Banks and other finance organisations have high barriers to entry because they are required to screen their customers, and only let the right ones in. If a bank cannot verify the identify of a person, or has reason to believe the person is likely to commit a crime, they are required to not service them.

Transparent: Most crypto transactions are recorded on public blockchains that are visible to everyone

Crypto enthusiasts tout the benefits of transparency, but I doubt any of them would want their banks to publish all their transactions. Traditional companies are not transparent, not because they cannot be, but because no-one would sign up as a customer (plus it would be, of course, dead illegal).

Microtransactions: Any small businesses do not accept credit cards because they would lose too much money in fees when selling low-priced goods

The article argues that crypto transactions are purely digital, and so their cost should approach zero. This is nonsense — what does it mean for a transaction to be purely digital? Traditional transactions do not have higher variable costs because they are analogue, but because (all together now) they need to cover regulatory and consumer protection costs.

Egalitarian: All participants in the cryptocurrency financial system are treated the same. Organisations that are part of new industries will be able to be banked

Again, the fact that traditional finance excludes some industries is a choice, not a bug; and the fact that crypto cannot do the same ought to be viewed as a downside — I imagine that even crypto enthusiasts aren’t happy that there is no way to exclude child pornographers from participating in the ecosystem.

The article lists a few other crypto benefits, which are in my view imaginary. All this is not to say that crypto doesn’t have (or will not have in the future) real benefits over traditional finance; but I think the above makes it clear that these benefits are derived almost in their entirety from constraints that we, not technology, have placed on finance.

(There are a few exceptions — crypto systems can be set up in such a way that their rules are automatically enforceable and irrevocable, which can be a good thing or a bad thing.)

The fact that crypto circumvents these constraints isn’t necessarily a bad thing. Many believe that the regulations imposed on banks and finance companies have gone too far, and that the cost they impose on society (in that, for example, many people are under-banked, or that immigrants cannot open accounts, or that sending money to some countries is prohibitively expensive, etc) is higher than the benefits. Changing regulations is difficult; forcing change by rendering them effectively unenforceable may be the easiest way forward.

But if this the value proposition of crypto, we need to be clear about it, and have a serious discussion about whether it is true that the costs of regulation exceeds its benefits, and stop touting crypto’s advantages as the result of brilliant technological innovation.

If you liked this post, you can follow me on LinkedIn or Twitter, or subscribe!