Solving the wrong problems

Tech & planning & DOGE

If all you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail

Thus (though not in these exact words) spoke Abraham Maslow. As is the case with most biases, even the smartest people in the world are not immune to this law of the instrument.

People who work in tech are a great case in point: they see the transformational powers of technology, and the analogue and inefficient ways in which much of the world operates, and assume there are huge gains to be had by ‘disrupting’ antiquated industries and processes.

To be sure, they are right in their assumption that technology (and know-how) can improve a huge number of things. But too often, the benefits from such improvements are immaterial in the grand scheme of things: the problems they solved were just not very consequential.

Attitudes towards Excel are a great case in point, in two ways. First, you have graveyards filled with defunct start ups that attempted to disrupt Excel [citation needed]. They’ve all failed, because the weaknesses they perceived in the software were ultimately not very costly, whereas taking the time to learn how to use an entirely new tool would be taken out of the time to crunch M&A deals. Hardly worth the trade off.

Second, tech execs have an instinctive disdain towards anything that whiffs of 90s/2000s technology: they consider it a sign of lazy, backwards, dinosaurian thinking. In an example of treating a symptom instead of a cause, this causes them to focus on changing technology rather than solving the problem the technology is being used to solve in the first place. I recently received a call from a friend who’s been asked to use AI to fix their company’s planning process; the senior leadership in his company feel that the tech currently used for planning is old and unfit for purpose. But here’s the thing: when it comes to planning, the process of putting together a plan matter waaaaay more than the tool used to do it. Changing tools without re-designing the process won’t achieve much. (See my previous post on what a high-tech planning process looks like in a tech company).

(In the same way, using Excel won’t get you a good answer if the thinking and the assumptions that go into your model are poor. One of the best finance managers I’ve known used to do analyses on paper (and even napkins) — I still have one of his efforts:

)

(Interlude 1: on planning

I have lots to say on planning, which will bore 99% of readers, so feel free to skip this parenthesis.

Most tech companies have bad planning processes for a few reasons. First, tech companies just don’t have very good finance managers (there are exceptions, so if you are a finance manager at a tech company, feel free to assume this generalisation does not apply to you!). Finance teams rank very low in the tech hierarchy, and so people who are strong in finance do better outside of tech.

Second, finance teams in tech companies are rarely integrated with business & products teams. When I was a finance manager at P&G, I always sat with my marketeers, sales managers, and engineers (when I worked in a factory). In the tech companies I worked, finance managers sat among themselves; they developed financial plans and projections with little and in some cases no input from GTM and product teams. Conversely, many commercial decisions hardly considered advice from finance teams — for instance, there was rarely finance input on which product features to prioritise building.

Third (and partly the reason for the second issue), product teams think that finance is a distraction and a bureaucratic burden: taking the time to give input to financial models and forecasts is time-consuming, and diverts focus from building & shipping new features. In my view though, the work that goes into a good finance model and a good business plan is exactly the same that should go into product building: to decide what to build next (what to prioritise among the many different ideas), you should be able to estimate the commercial impact of each option. So the work is not duplicative; you should be doing it anyway. (Yes, yes, there is some nuance here, product teams should be able to use judgement and not just base decisions on projections, the impact of some decisions is hard to estimate, and over-reliance on financial models can lead to short-term bias. All true — but going from ‘doing planning well is hard’ to ‘let’s not do planning at all’ is lazy.)

All which to say: if you think your company’s planning process is not fit for purpose, and it’s not actionable, then don’t jump to creating fancy new AI models to do it; instead, focus on integrating your planning/finance & business/products teams. If you achieve this, then you can get 90% of the value using Google sheets. Conversely, just because a company is using Excel, it doesn’t mean they don’t know what they’re doing.

For more on planning, I recommend Working Backwards.

)

(Interlude 2: solving the wrong problem can still be incredibly lucrative

For a long time, I thought that tech companies solving the wrong problem were foolish. But time and time again, I’ve seen companies prosper despite misunderstanding the problem they were solving, or by building an answer in search of a problem.

The most famous example of the latter is Amazon: Bezos didn’t start by asking how to best-sell books, he started by looking for a problem that the internet could help address, and built one of the most successful companies in history.

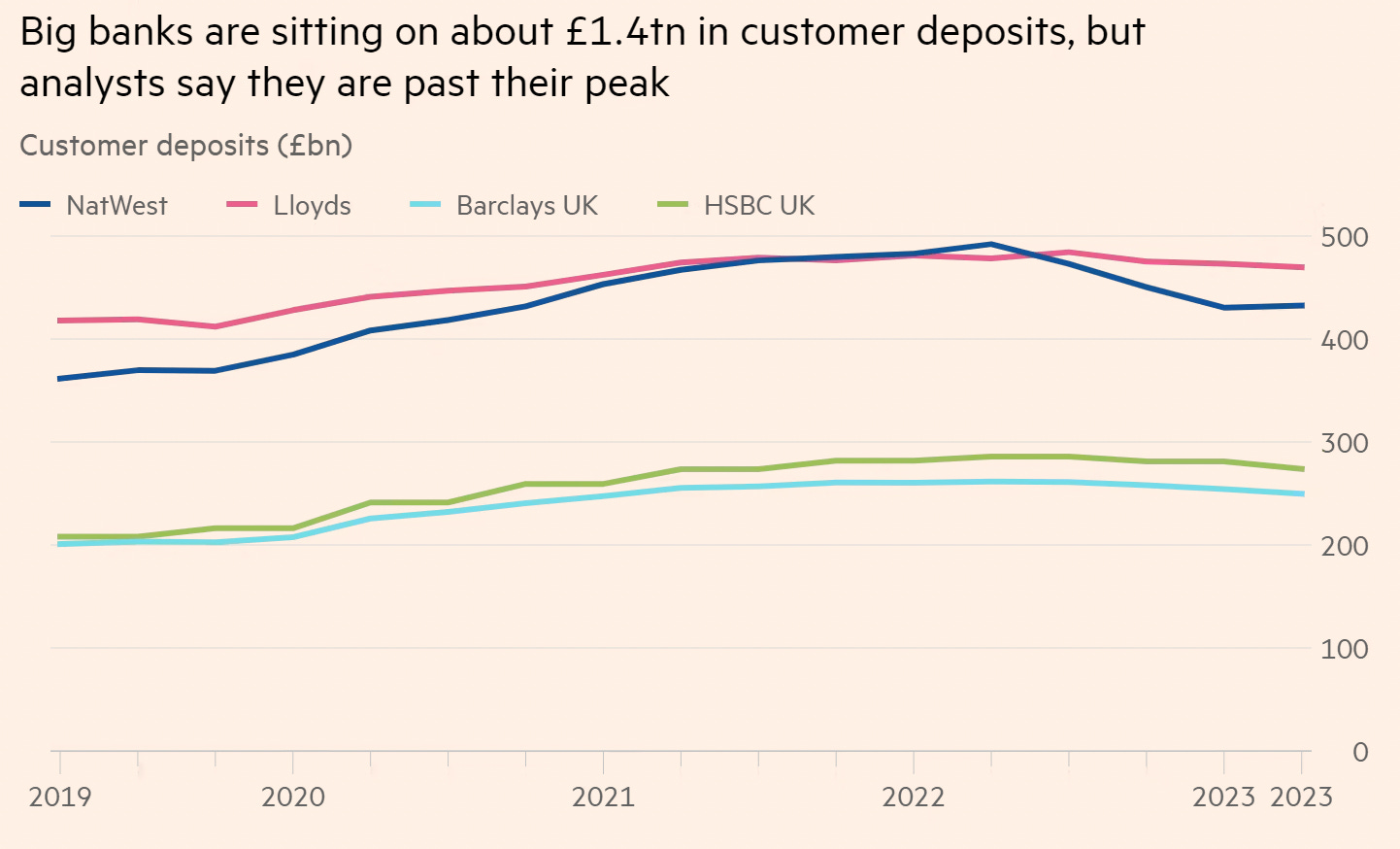

But there are many other examples of companies doing phenomenally well even though their leaders did not (in my view) really get their industries. Most fintechs fall in this category: for all their talk of how they’re disrupting a stale industry, most neobanks have low market share in terms of what actually matters: customer deposits. Though deposits in big banks have declined recently, that’s in response to the low interest rates they’re offering, not because of their bad app design and lack of innovative features (and, they’re still comfortably higher than they were in 2020):

Basically, fintech founders drastically overestimate consumers’ dissatisfaction with banking, and underestimate intertia. And in fact, my personal view is that a lot of the appeal of the neobanks is not their good design and tech stack (which is incomparably better than incumbents’!), but their lack of FX and other fees; in other words, their primary appeal is commercial, not tech-driven.

But nevertheless, these fintechs have done extremely well. Many are turning profitable, and command high valuations. And though they don’t really pose a threat to incumbents, they have spurred them to up their game. Sometimes, doing the wrong thing very well still pays.

)

On DOGE

DOGE’s failure to live up to its hype is also partly because of engineers’ habit to assume everything can be made 10x better with smarter thinking. I myself cheered for DOGE, and I still believe that to improve public services and cut costs we need a sense of urgency, and we need to perhaps over-correct for a while. But taking a sledgehammer to things like foreign aid, which is like 1% of the budget, won’t make a dent.

Drastically improving spend and services requires identifying the biggest spend buckets, and the most painful services, and addressing those. In countries like the US and the UK, the reason these have not been touched is not corruption, it’s not civil service incompetence, it’s not idiocy: it’s that these areas are politically contentious.

Take the UK: the biggest budget items are healthcare and pensions, with the former being a source of frustration as well (long waiting times, etc). Making changes to improve service and lower cost is not hard intellectually, but it’s impossible politically. Any party that actually cuts spend in these areas will not get re-elected for a generation. Tinkering at the margins by reducing fraud, or deploying nudge units, will not achieve much at all.

In other words: I stand by my previous statement that there is bloat and inefficiency and so on, and we should be reducing them as a matter of principle. But as a proportion of total spend, these are rounding errors.