I’ve been working in retail banking for the past three years, and I can confidently say that few people, including among those of us who work in the industry, understand how it works.

This post is a list of FAQ to help people understand finance; if you are among the extremely few people who are an expert in the field, you’re likely to spot over-simplifications and omissions (but not — I hope! — glaring errors); if you do, please comment below or email me and I’ll edit the post. Also, if f you have questions relating to banking or finance that are not covered here, please let me know and I’ll try to add them.

You don’t need to read these in order; feel free to jump to whichever FAQ you want an answer to! So, off we go:

What is the function of banking, and finance in general?

It is common for some people to claim that finance is a scam, a BS industry that adds no real value to the world, and exists merely to enrich Wall Street at the expense of main street.

This is not true. Finance is a huge industry, and the myriads of stakeholders in it provide a thousand different services, from building networks so that institutions such as banks can exchange information, to the physical printing of currency. But as a whole, I’d argue that finance serves two key functions, both of which are immensely valuable, and without which the world would be a far poorer place.

(It’s worth clarifying here what ‘wealth’ and ‘poverty’ mean, and how they differ from ‘money’. Wealth is a measure of the number and quality of the goods and services to which people have access. The more and better houses, cars, foodstuffs, drinks, shampoos, sound systems, TVs, etc we have, the richer we are. Money is a fiction (originally a form of debt) that is used as a store of value, a common unit for comparing the value of different things, and a mechanism of exchange. Money in itself is worthless, and it is therefore true that ‘just making money’ does not lead to an increase in wealth; some people seize on this fact to argue that the finance industry, which produces nothing tangible, is therefore non-value adding. But there are two mistakes here: first, not all wealth is tangible. My definition above included ‘service’ as wealth — having peace of mind, or convenience, are valuable things. Second, finance need not lead to a direct increase in material wealth — it does so indirectly, as I’ll explain.)

Finance’s two key functions are:

The reduction of risk, and,

The channeling of resources away from low wealth-producing projects to higher wealth-producing ones.

Finance reduces risk in all sorts of ways. The most obvious is insurance, where clients and customers will, on average, lose money to buy protection in case of catastrophic (or at least, bad) outcomes. But insurance is just a specific case of the more general way in which finance reduces risk: diversification. Insurers make money because even if a few clients end up costing them, most do not; similarly, banks give out many loans, so that though some people will default, the returns from the rest will more than offset that cost; investment firms will place money on different assets, so even if some perform poorly, the overall return will be positive; and so on. This ability to reduce risk increases wealth: first, individuals benefit directly from mitigating the risk (which is why most of us take out some form of insurance); second, it means people, companies, entire nations can raise capital to invest in productive activities.

Which brings us to the second function, resource allocation. Any company that makes money through investment (be it equity (investing in companies) or debt (both companies and individuals) tries to predict which investments will pay out; in doing so, it tries to find assets that will produce the best risk-adjusted return. And so, banks take deposits from customers (which in the absence of banks would be sitting under a mattress) and channel it to more productive users; investment managers channel money away from dying companies, and into ones that make better or cheaper products; VCs try to identify the companies that will make the biggest positive impact on the world (the fact they don’t always get it right doesn’t mean they don’t provide an immensely valuable service).

To an outsider, this might seem like moving money around, but someone needs to coordinate the work of deciding which companies should get resources and which shouldn’t. It’s not an easy job!

(All this said, it is of course true that some activities in finance are less value-adding than others. A lot of finance is gaming regulations and minimising tax; some of our brightest minds work on quant trading, which is less about resource allocation, and more about exploiting market inefficiencies. This provides liquidity and makes markets more efficient, which is valuable on aggregate, but as not directly value-adding as one might hope.

Then there’s speculation: a lot of money is changing hands, not in search of sustainable economic growth, but in the hope of number go up. (There’s an argument to be made here that pumping money in meme stocks and random crypto coins isn’t as obviously idiotic as it first seems: for some, it’s a form of entertainment, same way that going to a casino is. In this light, this kind of finance can again be seen as worthwhile, just not in the way we normally think it ought to be.)

And of course, there is outright fraud, but this is true with everything; it’s not finance-specific.

Also, some readers might object, have you ever met an investment banker? It sure doesn’t look like they do what they do from the goodness of their heart. It sure looks like greed is the motive here. First, yes, I’ve met plenty of investment bankers; and though doubtlessly money is a motivator, most of the people I know in finance are driven by more than that (admittedly, public service is not their highest motivator; people I know in finance just like the industry and the nature of the work, they like access to powerful people, they like working on projects that have a big impact on stakeholders (as M&A does, for instance: it’s often one of a CEO’s most impactful actions, so it feels cool being the one advising them on it and making it happen). But this is not to say that they lack integrity! Public service doesn’t have to be your number one driver for you to care about doing the right thing.)

But second and more important, an individual’s motivation doesn’t really matter: the fact that an investment banker is motivated by their bonus does not mean they do not provide a service. I’m sure there are many doctors who are in it for the money: they still save lives.)

What do banks actually do with customers’ money?

Simplified TL;DR: banks keep some of their customers’ money in cash in their own bank accounts (bank have their own accounts with their country’s central bank, but also with other banks), and some they invest.

For a more comprehensive account of what’s going on, let’s start with a quick introduction to accounting terms: an asset is something you own; a liability is something you have borrowed and need to return at some point. When a customer deposits £100 at their bank, the bank suddenly has £100 in assets, and £100 in liabilities: the asset comes in the form of the £100 that the bank now holds; the liability is because the bank ‘owes’ £100 to their customer — they have to return the money when the customer demands it. Most people don’t really think of it this way, but their deposits are really a loan to their bank.

The £100 is initially a cash asset, but banks do not hold all their assets in cash. If they did, they would only earn whatever interest their own bank accounts pay — which, until recently, was basically 0. Instead, they invest it, either by purchasing financial securities such as bonds, or by lending it out to their customers and clients — for instance, by providing mortgages, consumer loans, commercial loans, credit card balances, etc. Of course, they do keep some of their assets in cash, because they need to be able to return money to customers who want it.

One nuance here though: as we’ll see in the answer to the next question, when banks lend out money, they don’t literally move money out of their customers’ deposits to those of their debtors; they create new money.

The allocation to different kinds of assets varies by bank. For instance, in the UK, Monzo and Starling keep about half their assets in cash, whereas Natwest only keeps 20% of theirs in cash. (What Monzo (and Starling, to a lesser extent) is doing is known as narrow banking — it keeps most of its customers’ deposits in very safe assets that yield relatively low returns. Whether this is a good thing or not is debatable: on one hand, if every bank did this, the finance sector would be more stable and safe; on the other, there would be less money channeled to riskier but wealth-creating ventures.)

What is digital money?

Note that this means people do not ‘own’ money themselves, except for that they hold in actual cash; everything in their bank account is a claim on their bank.

You may have heard of central banks proposing the creation of digital money, which may have left you confused: isn’t most money digital already? The difference is that proposed digital currencies would be owned directly by individuals, and they’d represent a direct claim to a central bank — in the same way that Bitcoin works.

A well-designed digital money system would disintermediate banks to an extent, and could make transfers (see below) cheaper and faster — but there would also be downsides:

People would need a way to track their digital money, and this comes with risks: what if you lose access to it? What if someone steals it? And how can money sitting idle generate returns? The crypto industry has proven that for all the talk of sovereignty and disintermediation, people like to have institutions they can trust to park their assets — both for convenience and security.

Kind of linked to this, if people own their money directly, who enforces checks and balances when people transfer it? Whenever you make a bank or card payment, your bank and card networks run various checks to minimise the chances you’re being defrauded — if you hold your money directly, and can send it to whomever you want, who’ll perform these checks?

There are privacy concerns — digital currency can be tracked, in the same way that Bitcoin can: if I send you BTC, I learn your wallet’s address, and I can then track the payments you make.

These aren’t insurmountable, but they’re thorny problems to solve.

I’ve heard that banks create money — what does that mean?

Money comes in three forms. The one most of us think of when we think of ‘money’ — physical coins and notes — is only a tiny part of the total money supply, about 3% in the UK. The rest is reserves (the money banks keep in their own accounts at the central bank — about 18% of the money supply in the UK) and bank deposits (money consumers and companies keep in their own bank accounts — about 79% of the money supply in the UK).

Earlier I wrote that banks help channel deposits that would be sitting under a mattress to more productive uses; this is not quite right. Suppose your neighbour deposits £1,000 at your local (narrow) bank. The bank will record £1,000 in assets, which it keeps in its own account at the Bank of England, and £1,000 in liabilities, since it owes that money to your neighbour.

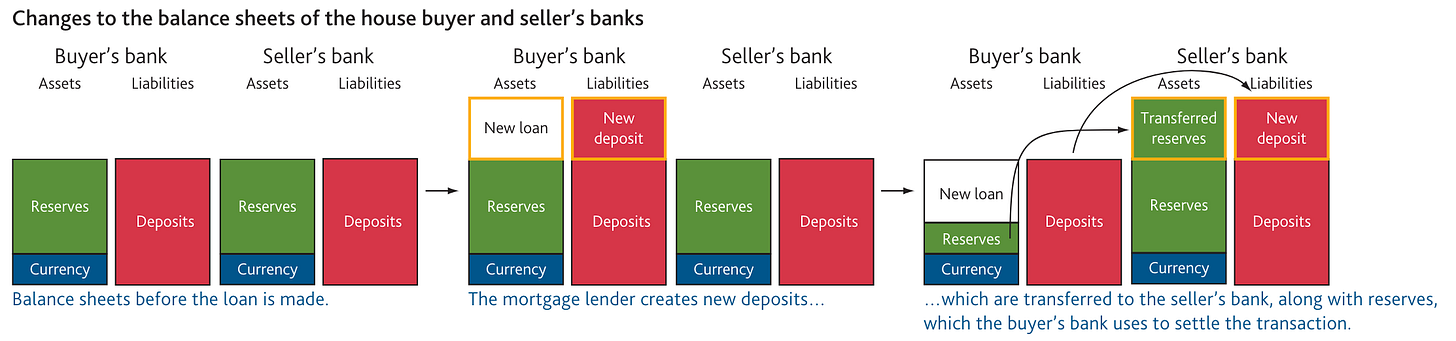

When you show up and ask for a £500 loan, the bank doesn’t draw money from its own account with the BoE. Instead, it simply updates your account to show a balance of £500. That money has been created out of thin air! The bank now still has reserves of £1,000, a new asset worth £500 (your loan) and liabilities worth £1,500 (the money in your neighbour’s and your account).

Now you may ask, why then don’t banks create infinite money? There are two constraints. One is capital requirements, which we’ll turn to next. The other is that when people spend their money, banks need to transfer money out of their reserves. If you spend £150 on an EasyJet flight, your bank needs to move that money to EasyJet’s account, which may be held at a different bank. For this to happen,

Your bank reduces your account balance

It reduces its own balance at the BoE

It increases EasyJet’s balance at the BoE by the same amount

EasyJet’s bank increases EasyJet’s balance.

And so, a bank with £1,000 in deposits cannot make loans of £100,000; if even 1% of this money were spent at merchants with banks accounts in other banks, it’d go broke. Note that this means banks with larger market share can create more money: the higher a bank’s market share, the more money will move between accounts held at the same bank.

The BoE has a very useful infographic on what this process looks like when a bank gives a customer a mortgage (you can read everything I’ve just explained in more detail here):

(To be a little more precise, the bank does not record the loan’s value at its principal amount; it takes into account expected losses from defaults. (This also means that as soon as the bank writes a loan, it has to recognise a loss in its income statement, equal to the expected losses from that loan.))

What are ‘capital requirements’?

Capital requirements are a restriction regulators place on banks. When banks make loans or other investments, they record these as assets on their books. However, assets are risky: people and companies and even governments can default on their loans, companies can go bankrupt, their share value going to zero, real estate may lose its value, and so on. If a bank has funded its acquisition of such assets solely by borrowing money itself, then its creditors (i.e. mainly its depositors) face a big risk: if the bank makes bad investments, the creditors will lose their money, whereas the bank’s shareholders will suffer no losses.

So regulators mandate that banks put their own (shareholders’) money on the line: they require that a certain percentage of a bank’s assets value comes from the bank’s equity (money it has raised from its shareholders) and retained earnings (its past profits).

In other words: if I start a bank, I cannot just take deposits and use them to make loans without taking any risk myself. I must risk at least some of my own money, to absorb any potential losses.

(To clarify this point a little: shareholders are entitled to any value a company has left after all other creditors have been paid. Suppose a bank has raised £100 from depositors, and made investments worth £100; if these investments lose £10 of their value, then depositors will get £90 back — i.e. they’ll lose money. But if the bank had raised £90 from depositors and £10 from its shareholders to make that £100 investment, the depositors would get all of their £90 back (and the investors would get nothing). That’s why equity investments are riskier than debt (but on the flipside, they have way higher upside: banks that lent money to Google in its early days got their investment + some interest; people who invested in Google stocks became millionaires).

Note that in most cases shareholders have limited liability: they can only lose what they put in (well, and the company’s retained earnings). But there are banks whose owners have unlimited liability: if the bank goes under, depositors can go after its owners’ personal assets. C. Hoare & Co, the UK’s oldest private bank, is an example of this.)

The practicalities of this are extremely thorny even for experts. First off, a bank’s assets are risk-weighted. Cash has a 0% risk weight — meaning that from a capital requirements standpoint, I could open a bank without any of my own money on the line, if all I did was take customers’ doubloons and kept them in my vault. Second, defining what capital counts towards meeting the requirements is tricky — it needs to account for all sorts of financial wizardry (e.g. convertible bonds; accounting gimmicks that impact earnings; etc). Third, ditto re assets: defining the risk associated with different kinds of assets is extremely complex; and to make things even more so, regulators have defined a standardised approach to valuing assets, but they can also grant banks permission to use their own internal models (though banks have to jump through a lot of hoops to be allowed to do so.)

If you want to understand these things in detail, you’ll probably need to study for a very dry Phd, and spend some time in Basel.

I’ve heard ‘banks borrow short to lend long’ — what does that mean?

This is an interesting one. As discussed earlier, customer deposits are really loans from consumers to banks. Technically, these loans have a short duration: the depositors can request their money back at any time, instantly (unless they are in fixed-term accounts). Banks use these deposits to make longer-term loans (e.g. mortgages, which have 10-30 year terms). (This is also known as ‘maturity transformation’.)

This works because though deposits have a short duration on paper, in practice they are very sticky: we rarely demand our banks to pay us out our entire balance. In any other context, it’d be incredibly risky for a company to borrow short to lend long: what happens if your creditors call their loan? You go bankrupt. Not that this doesn’t happen in banking — a bank run is when depositors rush to take out their deposits, leaving a bank insolvent. This is exactly what happened to Silicon Valley Bank, and to Northern Rock before it, not to mention the countless banks that went under in the Great Depression; but thanks to deposit guarantee schemes, it’s much rarer than it used to be.

How do banks make money?

Banks have several revenue streams, but usually the largest one is interest income — i.e. money they make on the loans they give.

(As mentioned earlier, the accounting for this is interesting: when banks make a loan, they recognise it on their balance sheet at the principal amount, less some upfront provisions for losses. So, if a bank lends you £1,000, it will record an asset of, say, £900 on its books. All interest you pay is recognised as revenue. What’s extremely important to understand is that the real fair value of the loan is not equal to £1,000 or £900: the fair value of the loan is the sum of its expected cash flows, discounted by an appropriate interest rate. To translate this in English: suppose you lend someone £1,000, and they promise to repay that £1,000 in ten years; in the meantime, they will pay you £300 per year in interest. Suppose also that that person is guaranteed to not default on their loan. Would you sell me that loan for £1,000? Of course not! £300 per year for ten years is worth £3,000. Of course, £3,000 over ten years (plus the £1,000 principal repayment in 10 years) is worth less than £3,000 now — this is where discounting comes in. But even with a high discount, the fair value of that loan is higher than £1,000.

But, banks do not account for loans at fair value. If they did, they would have to recognise gains and losses every time interest rates (which is what they use to discount future cash flows) change. This would result in far more volatile earnings for banks: rather than booking revenue tied to their customers’ monthly repayments, they’d be booking revenue or losses based on the macroeconomic climate. And it might also result in huge surprise losses.)

Besides interest, banks can also make money from:

Interchange: every time you use your debit or credit card, the bank is paid something like 0.2%-0.3% of the value of the transaction by the card company (Visa or Mastercard); this is called interchange. (Interesting factoid: if you’re wondering why rewards cards (such as those that give you cashback) are much more prevalent in the US than in Europe, the answer is that interchange is capped by law in Europe. In the US, interchange can be as high as 2%, and so banks have more money to play with, and pass back to their customers.)

Other financial services: banks often offer insurance, brokerage, and so on.

Note that though interest is the largest revenue source for most banks, it has a downside compared to some of the other sources: to generate interest, a bank has to buy/create assets (mainly loans), which are subject to capital requirements. So banks need more capital to generate interest income.

(Of course, this is all about retail banks; investment banks make money by charging fees to provide various services and advice to companies.)

How do bank transfers work?

Payment systems vary across the world; here I’ll describe the main ones in the UK, of which there are three: CHAPS, BACS, and FPS. CHAPS is administered by the Bank of England; BACS and FPS are run by Pay.UK, a very peculiar non-profit entity that doesn’t even have a Wikipedia page. Think about that: there are Wikipedia pages for Love Island participants, but not for the organisation running the UK’s most-used bank transfer services.

CHAPS

CHAPS (Clearing House Automated Payment System) is the simplest system to understand. It accounts for only 0.5% of payment transactions, but over 90% of payment value in the UK. CHAPS payments are basically high-value real-time payments, which are cleared and settled individually using the BoE’s own infrastructure (‘clearing’ refers to the agreement between various stakeholders that it’s safe to process the transaction; ‘settlement’ refers to the actual movement of money. As we will see with FPS, this is not always simultaneous.)

The way they work is that some financial institutions are registered as CHAPS direct participants with the BoE. They hold settlement accounts with the bank (which, incidentally, can be the same as their reserve accounts explained earlier; a bank can choose to only have a settlement account, but I’ve no idea why a bank might choose to do that. A settlement-only account would earn no interest from the BoE.)

When person A sends money to person B via CHAPS, person A’s bank sends money from its own settlement account at the BoE to the settlement account of person B’s bank. At the same time, of course, it reduces person A’s balance.

(Note that that this ignores any fees that the banks pay the BoE, or that the banks charge their customers.)

So this is pretty straightforward. FPS is a bit more convoluted.

FPS

FPS is used to process low-value (up to £1m) transactions; it makes up a much smaller % of the value of transfers in the UK, but it accounts for the majority of number of transfers.

As is the case with CHAPS, FPS payments are settled using settlement accounts in the Bank of England. But on any given day, there will be a huge number of transactions back and forth between customers of different banks; rather than settle each of these individually, banks aggregate these payments and settle the net amounts (there are three settlement points per day). Schematically:

The role of Pay.UK in all this is to facilitate the exchange of information between banks (which helps them clear the amounts), including laying out processes for recovering money in case of mistakes.

BACS

BACS (Bankers’ Automated Clearing System) is used for processing batch payments. This happens when companies want to make multiple payment at once — most commonly, to pay salaries — or when they want to take payment from customers (via direct debit).

The way it works is that some companies are registered as BACS Service Users, meaning they can submit files with payment details directly to BACS. They send such files on their own behalf, or on behalf of their clients, and the payments are processes in 3-day cycles:

On Day 1, service users send the payment files to BACS

On Day 2, BACS processes the payments, runs checks, etc

On Day 3, the payments are cleared and settled (as usual, settlement happens via the Bank of England)

International payments

This is where things get really complex, and I’d be lying if I said I have a firm grasp of the process; here’s my best attempt at explaining international transfers.

Banks maintain reciprocal relationships with other banks across boarders by opening the needlessly exotically-named nostro and vostro accounts.

A Nostro account is one held by a domestic bank, in another bank abroad. For example, NatWest in the UK may have a USD-denominated Nostro account with Citibank in the US.

Conversely, a Vostro account is one held by a foreign bank, in a domestic bank. For example, Citibank may have GBP-denominated Vostro account with NatWest.

When a British resident wants to send £1,000 to an American, what happens is that Natwest asks Citibank to make that payment on their behalf. To fund it, Citibank will reduce NatWest’s Nostro account by the USD equivalent of £1,000, and increase their American customer’s balance by the same amount. In the UK, of course, NatWest will similarly decrease their own customer’s balance by £1,000. Of course, this assumes that the American happens to be a Citibank customer; if they are not, Citibank will clear and settle the payment via the normal US payment methods (of which I know nothing about).

But this gets more complicated when you remember that there are many countries in the world, with wildly different regulatory and banking systems; maintaining such reciprocal relationships across the globe is hard, and kind of unnecessary: there’s no need for a Greek bank to have a relationship with a bank in Nepal — how often do Greeks transfer money there? So on the rare occasion where a Greek does want to do that, the money will have to follow a longer trail: the Greek bank will have to find a bank with which it already has a Nostro account, and which has itself a Nostro account with a bank in Nepal. And if it doesn’t find one, it will have to go through another link in the chain. (This whole process is known as correspondent banking.)

This is where SWIFT comes in. Contrary to what most people think, SWIFT isn’t a payments system: it’s a communications protocol. It helps banks transmit messages about international transfers in a consistent format. It is neither a clearing nor a settlement process — as explained, the actual transfers happen via Nostro accounts.

In recent years, some companies (such as Wise) have begun integrating directly with the payment systems of many different countries. This removes the need for correspondent banking: the way Wise works is that when you send a payment from the UK to the US, you pay the money to a Wise legal entity in the UK, and Wise pays out the equivalent amount from a legal entity in the US. You might wonder why large multinational banks with presence in many countries do not do this themselves. I wonder that too — I don’t have a good answer. I think the reason is partly that such banks maintain different infrastructure in the different countries they operate (either because they entered new markets by acquiring other existing banks, or because they build their infrastructure in each new market from scratch to comply with local requirements), and getting their different international systems to talk to each other is very difficult. But this is just a guess.

Other companies (e.g. Sling, which I encourage you to try!) eschew traditional payment rails altogether, managing transfers via stablecoins. This works by letting customers buy a stablecoin — i.e. a cryptocoin that is pegged to some currency, e.g. the USD or GBP. Transferring ownership of stablecoins is done via crypto protocols; and converting stablecoins to fiat currency is done via off-ramps — a service provided by various entities (e.g. crypto exchanges, payments processors) for converting money to crypto and vice-versa.

In that infographic from the BOE it shows that when the buyer pays the seller for the house, the reserves drop in the originating bank to below the deposit level. Is that correct, what am I missing.