Things can be expensive and underpriced at the same time

On the latest Ticketmaster twitterstorm

The latest crusade on X is against Ticketmaster’s CEO’s comment that concert tickets are underpriced. Entirely predictably, people are upset and think that his comment proves he’s out of touch.

But the fact that tickets are underpriced is obvious, given that most tickets can fetch multiples of their value in the secondary market. The issue here is that most people think underpriced means the same as cheap; it doesn’t, in exactly the same way that overpriced doesn’t necessarily mean expensive. Underpriced, in the context used by Ticketmaster’s CEO, means that concert tickets could go for a far higher price without causing a big drop in demand — at least, not such a large drop that raising prices would become unprofitable. In other words, at current prices, concert venues, artists, and Ticketmaster are leaving money on the table.

I don’t think anyone who’s upset with Ticketmaster would dispute that tickets are underpriced under this definition; and even if they did, well, the argument made by Ticketmaster is easily falsifiable. If Ticketmaster increases prices and its revenue goes down as a result (or more accurately, profit), then critics will have been proven correct, and Ticketmaster will quickly decrease prices again. So there’d be nothing to be upset about.

The real problem these critics have is that they believe prices ought to be lower. I understand why people might feel this way: we all would like to pay less for things we like. But I want to investigate here to what extent critics can develop a coherent worldview around their emotive response. So let’s look at some assumptions that can underpin a rational argument that prices are too high.

(I am going to overlook arguments stemming from a fundamental misunderstanding of demand and supply. But it is worth reminding everyone that when a lot of people want something that is in short supply, that thing’s price will be high. Artificially restricting price will cause shortages, because too many people will want the thing, but there won’t be enough of it. Indeed, this is what does happen with concert (and theatre) tickets: they sell out immediately, and even people willing to pay far higher prices cannot get one.1)

First, some people argue that the market is not competitive: prices are too high because Ticketmaster is a monopoly. In a way, these critics are partly right, but not in the way they think. Ticketmaster itself isn’t a natural monopoly (at least, not in any way I can think of). Other companies could easily imitate its business model, set up a website, and sell tickets at a lower price. There’s nothing to stop entrepreneurs from doing this, especially in a world flush with VC dollars. What is in limited supply is the number of superstar artists. There is only one Taylor Swift, and only a handful of other stars in her league. No matter which platform markets her tickets, these tickets will always command a ridiculously high price.

This leads to a second line of reasoning, which is that tickets can be said to be overpriced relative to their intrinsic value. Is it worth paying hundreds or thousands of dollars to see Taylor Swift perform? I mean… clearly yes, to some people. This is a pretty fundamental difference between those who believe in free markets and those who believe in socialism. The former believe there is no intrinsic value to anything beyond what someone is willing to pay for it. The latter think there are objective ways of determining value (e.g. labour theories of value, or simply the opinion of a more educated, smarter elite (if you think concert ticket prices are too high, and ought to be capped, or Ticketmaster ought to be broken up, etc, what do you think is a reasonable ticket price? How do you arrive at that figure, and why should I agree with it?)). This is hard to adjudicate in a short blogpost, but I have a very strong aversion to people thinking they know better than someone how much that someone should value something. I do understand the inclination to do so: I too see many people make bad choices in their lives, and there are countless examples of widespread idiocy (Fyre Festival). But I also think that if we start pulling on this thread, it’s not only capitalism that will unravel but also democracy. Best not go there: in our current system, some people will make bad choices, but that’s infinitely better than not letting people make their own good choices.

The third, and most defensible argument I can think of (and one to which I myself subscribe to an extent), is a blend of two bad arguments we’ve reviewed already, the misunderstanding of supply and demand and intrinsic value. Much like some blended whiskies are better than the single malts that comprise them, this blend is more cohesive than the two underlying arguments. To understand why, start with the free market rejoinder to the bad arguments I’ve outlined: ‘who are you to say what ticket prices should be worth to someone? If I’m willing to pay £1,000 to see Taylor Swift, who are you to tell me the ticket isn’t worth that much intrinsically? And, how can you even claim the ticket isn’t worth all that much, since you’re also arguing that attending concerts is almost a human right that deserves government intervention to protect? No, no. The only intrinsic value of a ticket is the amount someone is willing to pay for it, and ironically, it’s capping prices (which is what you’re suggesting) that will result in unfair pricing: some people will get a ticket for less than it’s actually worth to them (e.g. they will pay £500 and they would have been happy to pay £1,000); and, conversely, some people will end up not getting a ticket even though it’s worth more to them.’ The weakness here though is that free marketers equate willingness to pay with intrinsic value, ignoring ability to pay. A Taylor Swift ticket might be worth £1,000 to me, in the sense that if I had £1,000 I would absolutely pay it. But I don’t, and it’s unfair to say that someone who is richer than me values the tickets more than me. Taking this into consideration, we can agree that price caps can lead to the misallocation that free marketers are talking about, but that they also give the opportunity to poorer people to buy something they’ll enjoy more than a richer person.

Like I said, I am sympathetic to this argument. The problem with it is that, pragmatically, it’s impossible to know what people’s intrinsic values are, and how much they’d pay for tickets if they were richer. (Although there are some ways around this: artists and ticket sellers could give discounts people willing to prove their desire for a ticket in some way, e.g. through competitions, etc). And I think there are many downsides with price capping: it’s not just the misallocation of value among concert-goers; there’s also misallocation among artists. It’s hard enough for a newcomer singer to compete with Taylor Swift; it becomes even harder if Taylor Swift tickets are kept artificially cheap. Ditto re music venues, theatres, and all other kinds of entertainments.

In conclusion, I think that people complaining about high ticket prices are mostly misguided, and are responding emotionally, not rationally. The fundamental issue is there are too many people wishing to see too few artists perform. Capping prices does harm to the music ecosystem (after all, most artists are earning too little!). But free marketers are also too quick to dismiss the legitimate concern that someone rich can afford to pay a high price for something they really don’t value as much as someone less well off. As always, a little more goodwill on both sides would help us all understand the world a bit better.

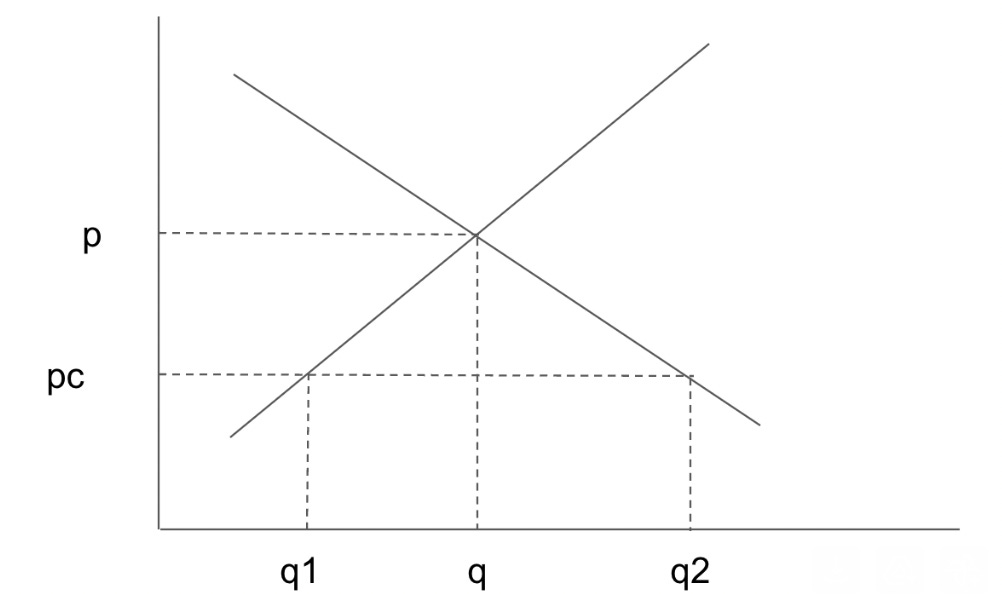

However, I have a nit-picky point to make here: economists overstate the amount of shortages caused by price caps. Looking at the demand-and-supply chart below, standard economic theory is that introducing a price cap of pc causes shortages of q2-q1: there is a demand for q2 units of a good, but only a supply of q1. But! The free market would have settled at a price of p and q. So, in my view, the ‘real’ shortage, is only q2-q1: the difference between the demand at the restricted price minus the supply that a free market would have produced.